OK Let’s Go: Three Approaches to Structuring Go Code

Aviv Carmi

The Go language was first announced in late 2009, and officially released in 2012, but has only started gaining serious traction in the last several years. It was one of the fastest growing languages of 2018, and is the third most wanted programing language of 2019.

Being relatively new, the Go community is not yet very strict about coding guidelines. If we take a look at coding conventions of communities that have been around for longer, Java for instance, we find most projects have a similar structure. This can be very helpful when writing big code bases, yet a lot of people would argue that for modern use-cases this can be counterproductive. As we advance towards writing micro systems and maintain smaller code bases, Go flexibility regarding project structure has a lot to offer.

We’ve all seen the Golang hello world http example in contrast to other languages like Java. There isn’t a dramatic difference between the two in terms of complexity nor in the amount of code. However, it shows the fundamental differences in the approach Go encourages us to take – when possible, write simple code. Ignoring the Object Oriented aspects of Java, I think the most important take from these code snippets is that Java requires creating a dedicated instance for each operation (HttpServer instance) while Go encourages you to use a global singleton.

This implies that you’ll have less code to maintain, fewer references to pass around. If you know you’re going to create only one server (which is usually the case) why work so hard? This philosophy becomes very powerful as your code base grows. Still, life can be tough This is because there are still several levels of abstraction to choose from, and mistakenly combining those may hold serious pitfalls.

…But don’t worry, at HUMAN, we’re here to help!

I’ll highlight three approaches to organizing and structuring your Go code. Each approach introduces a different level of abstraction. Then, I’ll compare them all and cover the use cases for each one.

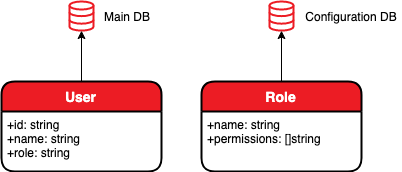

Our goal is to implement an HTTP server containing user information (Main DB in the figure below), where each user has a role (e.g. basic, moderator, admin), with an additional database (Configuration DB in the figure below), containing sets of permissions available for each role (e.g. read, write, edit). Our HTTP server should implement an endpoint that returns a set of permissions for a given user ID.

Let’s further assume that the configuration DB rarely changes and has long loading times, so we want to maintain it in-memory, load it once the server starts, and refresh it once per hour.

The entire code can be found in the article repository on GitHub.

Approach I: Single Package

The single package approach introduces a flat hierarchy, in which the entire server is implemented in one package. Full code.

Note: the comments in the code snippets are important for understanding the principles of each approach.

/main.go

<span class="token keyword">package</span> main

<span class="token keyword">import</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>

<span class="token string">"net/http"</span>

<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token comment">// As noted above, since we plan to only have one instance</span>

<span class="token comment">// for those 3 services, we'll declare a singleton instance,</span>

<span class="token comment">// and make sure we only use them to access those services.</span>

<span class="token keyword">var</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>

userDBInstance userDB

configDBInstance configDB

rolePermissions <span class="token keyword">map</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token builtin">string</span>

<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token keyword">func</span> <span class="token function">main</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token comment">// Our singleton instances will later be assumed</span>

<span class="token comment">// initialized, it is the initiator's responsibility</span>

<span class="token comment">// to initialize them.</span>

<span class="token comment">// The main function will do it with concrete</span>

<span class="token comment">// implementation, and test cases, if we plan to</span>

<span class="token comment">// have those, may use mock implementations instead.</span>

userDBInstance <span class="token operator">=</span> <span class="token operator">&</span>someUserDB<span class="token punctuation">{</span><span class="token punctuation">}</span>

configDBInstance <span class="token operator">=</span> <span class="token operator">&</span>someConfigDB<span class="token punctuation">{</span><span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token function">initPermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span>

http<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">HandleFunc</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token string">"/"</span><span class="token punctuation">,</span> UserPermissionsByID<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

http<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">ListenAndServe</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token string">":8080"</span><span class="token punctuation">,</span> <span class="token boolean">nil</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token comment">// This will keep our permissions up to date in memory.</span>

<span class="token keyword">func</span> <span class="token function">initPermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

rolePermissions <span class="token operator">=</span> configDBInstance<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">allPermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token keyword">go</span> <span class="token keyword">func</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token keyword">for</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

time<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">Sleep</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>time<span class="token punctuation">.</span>Hour<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

rolePermissions <span class="token operator">=</span> configDBInstance<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">allPermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span><span class="token keyword">package</span> main

<span class="token comment">// We use interfaces as the types of our database instances</span>

<span class="token comment">// to make it possible to write tests and use mock implementations.</span>

<span class="token keyword">type</span> userDB <span class="token keyword">interface</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token function">userRoleByID</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>id <span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token builtin">string</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token comment">// Note the naming `someConfigDB`. In actual cases we use</span>

<span class="token comment">// some DB implementation and name our structs accordingly.</span>

<span class="token comment">// For example, if we use MongoDB, we name our concrete</span>

<span class="token comment">// struct `mongoConfigDB`. If used in test cases,</span>

<span class="token comment">// a `mockConfigDB` can be declared, too.</span>

<span class="token keyword">type</span> someUserDB <span class="token keyword">struct</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span><span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token keyword">func</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>db <span class="token operator">*</span>someUserDB<span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token function">userRoleByID</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>id <span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token builtin">string</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token comment">// Omitting the implementation details for clarity...</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token keyword">type</span> configDB <span class="token keyword">interface</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token function">allPermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token keyword">map</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token builtin">string</span> <span class="token comment">// maps from role to its permissions</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token keyword">type</span> someConfigDB <span class="token keyword">struct</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span><span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token keyword">func</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>db <span class="token operator">*</span>someConfigDB<span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token function">allPermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token keyword">map</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token builtin">string</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token comment">// implementation</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span><span class="token keyword">package</span> main

<span class="token keyword">import</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>

<span class="token string">"fmt"</span>

<span class="token string">"net/http"</span>

<span class="token string">"strings"</span>

<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token keyword">func</span> <span class="token function">UserPermissionsByID</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>w http<span class="token punctuation">.</span>ResponseWriter<span class="token punctuation">,</span> r <span class="token operator">*</span>http<span class="token punctuation">.</span>Request<span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

id <span class="token operator">:=</span> r<span class="token punctuation">.</span>URL<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">Query</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token string">"id"</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token number">0</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span>

role <span class="token operator">:=</span> userDBInstance<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">userRoleByID</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>id<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

permissions <span class="token operator">:=</span> rolePermissions<span class="token punctuation">[</span>role<span class="token punctuation">]</span>

fmt<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">Fprint</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>w<span class="token punctuation">,</span> strings<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">Join</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>permissions<span class="token punctuation">,</span> <span class="token string">", "</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>Note we still use separate files to divide different responsibilities. This makes it more readable and easier to maintain.

Approach II: Coupled Packages

In this approach we introduce packages. A package should have sole responsibility over some behavior. Here we allow packages to interact with each other, thus needing to maintain less code. Still, we have to make sure we’re not breaking the principle of responsibility to ensure each piece of logic is implemented completely in a single package. Another important guideline for this approach is that since Go disallows circular dependencies between packages, we have to create a neutral package containing only bare definitions of interfaces and singleton instances. This will ensure our code is free from circular dependencies. Full code.

<span class="token keyword">package</span> main

<span class="token comment">// Note how the main package is the only one importing</span>

<span class="token comment">// packages other than the definition package.</span>

<span class="token keyword">import</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>

<span class="token string">"github.com/myproject/config"</span>

<span class="token string">"github.com/myproject/database"</span>

<span class="token string">"github.com/myproject/definition"</span>

<span class="token string">"github.com/myproject/handler"</span>

<span class="token string">"net/http"</span>

<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token keyword">func</span> <span class="token function">main</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token comment">// This approach also uses singleton instances, and</span>

<span class="token comment">// again it's the initiator's responsibility to make</span>

<span class="token comment">// sure they're initialized.</span>

definition<span class="token punctuation">.</span>UserDBInstance <span class="token operator">=</span> <span class="token operator">&</span>database<span class="token punctuation">.</span>SomeUserDB<span class="token punctuation">{</span><span class="token punctuation">}</span>

definition<span class="token punctuation">.</span>ConfigDBInstance <span class="token operator">=</span> <span class="token operator">&</span>database<span class="token punctuation">.</span>SomeConfigDB<span class="token punctuation">{</span><span class="token punctuation">}</span>

config<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">InitPermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span>

http<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">HandleFunc</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token string">"/"</span><span class="token punctuation">,</span> handler<span class="token punctuation">.</span>UserPermissionsByID<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

http<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">ListenAndServe</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token string">":8080"</span><span class="token punctuation">,</span> <span class="token boolean">nil</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span><span class="token keyword">package</span> definition

<span class="token comment">// Note that in this approach both the singleton instance</span>

<span class="token comment">// and its interface type are declared in the definition</span>

<span class="token comment">// package. Make sure this package does not contain any</span>

<span class="token comment">// logic, otherwise it might need to import other packages</span>

<span class="token comment">// and its neutral nature is compromised.</span>

<span class="token keyword">var</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>

UserDBInstance UserDB

ConfigDBInstance ConfigDB

<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token keyword">type</span> UserDB <span class="token keyword">interface</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token function">UserRoleByID</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>id <span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token builtin">string</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token keyword">type</span> ConfigDB <span class="token keyword">interface</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token function">AllPermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token keyword">map</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token builtin">string</span> <span class="token comment">// maps from role to its permissions</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span><span class="token keyword">package</span> definition

<span class="token keyword">var</span> RolePermissions <span class="token keyword">map</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token keyword">package</span> database

<span class="token keyword">type</span> SomeUserDB <span class="token keyword">struct</span><span class="token punctuation">{</span><span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token keyword">func</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>db <span class="token operator">*</span>SomeUserDB<span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token function">UserRoleByID</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>id <span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token builtin">string</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token comment">// implementation</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span><span class="token keyword">package</span> database

<span class="token keyword">type</span> SomeConfigDB <span class="token keyword">struct</span><span class="token punctuation">{</span><span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token keyword">func</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>db <span class="token operator">*</span>SomeConfigDB<span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token function">AllPermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token keyword">map</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token builtin">string</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token comment">// implementation</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span><span class="token keyword">package</span> config

<span class="token keyword">import</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>

<span class="token string">"github.com/myproject/definition"</span>

<span class="token string">"time"</span>

<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token comment">// Since the definition package must not contain any logic,</span>

<span class="token comment">// managing configuration is implemented in a config package.</span>

<span class="token keyword">func</span> <span class="token function">InitPermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

definition<span class="token punctuation">.</span>RolePermissions <span class="token operator">=</span> definition<span class="token punctuation">.</span>ConfigDBInstance<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">AllPermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token keyword">go</span> <span class="token keyword">func</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token keyword">for</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

time<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">Sleep</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>time<span class="token punctuation">.</span>Hour<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

definition<span class="token punctuation">.</span>RolePermissions <span class="token operator">=</span> definition<span class="token punctuation">.</span>ConfigDBInstance<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">AllPermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>/handler/user_permissions_by_id.go

<span class="token keyword">package</span> handler

<span class="token keyword">import</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>

<span class="token string">"fmt"</span>

<span class="token string">"github.com/myproject/definition"</span>

<span class="token string">"net/http"</span>

<span class="token string">"strings"</span>

<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token keyword">func</span> <span class="token function">UserPermissionsByID</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>w http<span class="token punctuation">.</span>ResponseWriter<span class="token punctuation">,</span> r <span class="token operator">*</span>http<span class="token punctuation">.</span>Request<span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

id <span class="token operator">:=</span> r<span class="token punctuation">.</span>URL<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">Query</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token string">"id"</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token number">0</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span>

role <span class="token operator">:=</span> definition<span class="token punctuation">.</span>UserDBInstance<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">UserRoleByID</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>id<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

permissions <span class="token operator">:=</span> definition<span class="token punctuation">.</span>RolePermissions<span class="token punctuation">[</span>role<span class="token punctuation">]</span>

fmt<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">Fprint</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>w<span class="token punctuation">,</span> strings<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">Join</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>permissions<span class="token punctuation">,</span> <span class="token string">", "</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>Approach III: Independent Packages

In this approach we also organize our project in packages. Here, each package must declare all of its dependencies locally via interfaces and variables. This makes it completely unaware of other packages. In this approach, the definition package from the previous approach is actually spread between all the other packages; each package declaring its own interface for every service. This may seem as an annoying duplication at first glance, but it isn’t. Each package that uses a service should declare its own interface, specifying only what it requires from it, omitting the rest. Full code.

<span class="token keyword">package</span> main

<span class="token comment">// Note how the main package is the only one importing</span>

<span class="token comment">// other local packages.</span>

<span class="token keyword">import</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>

<span class="token string">"github.com/myproject/config"</span>

<span class="token string">"github.com/myproject/database"</span>

<span class="token string">"github.com/myproject/handler"</span>

<span class="token string">"net/http"</span>

<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token keyword">func</span> <span class="token function">main</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

userDB <span class="token operator">:=</span> <span class="token operator">&</span>database<span class="token punctuation">.</span>SomeUserDB<span class="token punctuation">{</span><span class="token punctuation">}</span>

configDB <span class="token operator">:=</span> <span class="token operator">&</span>database<span class="token punctuation">.</span>SomeConfigDB<span class="token punctuation">{</span><span class="token punctuation">}</span>

permissionStorage <span class="token operator">:=</span> config<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">NewPermissionStorage</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>configDB<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

h <span class="token operator">:=</span> <span class="token operator">&</span>handler<span class="token punctuation">.</span>UserPermissionsByID<span class="token punctuation">{</span>UserDB<span class="token punctuation">:</span> userDB<span class="token punctuation">,</span> PermissionsStorage<span class="token punctuation">:</span> permissionStorage<span class="token punctuation">}</span>

http<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">Handle</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token string">"/"</span><span class="token punctuation">,</span> h<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

http<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">ListenAndServe</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token string">":8080"</span><span class="token punctuation">,</span> <span class="token boolean">nil</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span><span class="token keyword">package</span> database

<span class="token keyword">type</span> SomeUserDB <span class="token keyword">struct</span><span class="token punctuation">{</span><span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token keyword">func</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>db <span class="token operator">*</span>SomeUserDB<span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token function">UserRoleByID</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>id <span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token builtin">string</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token comment">// implementation</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span><span class="token keyword">package</span> database

<span class="token keyword">type</span> SomeConfigDB <span class="token keyword">struct</span><span class="token punctuation">{</span><span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token keyword">func</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>db <span class="token operator">*</span>SomeConfigDB<span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token function">AllPermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token keyword">map</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token builtin">string</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token comment">// implementation</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span><span class="token keyword">package</span> config

<span class="token keyword">import</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>

<span class="token string">"time"</span>

<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token comment">// Here we declare an interface representing our local</span>

<span class="token comment">// needs from the configuration db, namely,</span>

<span class="token comment">// the `AllPermissions` method.</span>

<span class="token keyword">type</span> PermissionDB <span class="token keyword">interface</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token function">AllPermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token keyword">map</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token builtin">string</span> <span class="token comment">// maps from role to its permissions</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token comment">// Then we export a service than will provide the</span>

<span class="token comment">// permissions from memory, to use it, another package</span>

<span class="token comment">// will have to declare a local interface.</span>

<span class="token keyword">type</span> PermissionStorage <span class="token keyword">struct</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

permissions <span class="token keyword">map</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token builtin">string</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token keyword">func</span> <span class="token function">NewPermissionStorage</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>db PermissionDB<span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token operator">*</span>PermissionStorage <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

s <span class="token operator">:=</span> <span class="token operator">&</span>PermissionStorage<span class="token punctuation">{</span><span class="token punctuation">}</span>

s<span class="token punctuation">.</span>permissions <span class="token operator">=</span> db<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">AllPermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token keyword">go</span> <span class="token keyword">func</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token keyword">for</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

time<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">Sleep</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>time<span class="token punctuation">.</span>Hour<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

s<span class="token punctuation">.</span>permissions <span class="token operator">=</span> db<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">AllPermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token keyword">return</span> s

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token keyword">func</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>s <span class="token operator">*</span>PermissionStorage<span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token function">RolePermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>role <span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token builtin">string</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token keyword">return</span> s<span class="token punctuation">.</span>permissions<span class="token punctuation">[</span>role<span class="token punctuation">]</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>/handler/user_permissions_by_id.go

<span class="token keyword">package</span> handler

<span class="token keyword">import</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>

<span class="token string">"fmt"</span>

<span class="token string">"net/http"</span>

<span class="token string">"strings"</span>

<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token comment">// Declaring our local needs from the user db instance,</span>

<span class="token keyword">type</span> UserDB <span class="token keyword">interface</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token function">UserRoleByID</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>id <span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token builtin">string</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token comment">// ... and our local needs from the in memory permission storage.</span>

<span class="token keyword">type</span> PermissionStorage <span class="token keyword">interface</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

<span class="token function">RolePermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>role <span class="token builtin">string</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token builtin">string</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token comment">// Lastly, our handler cannot be purely functional,</span>

<span class="token comment">// since it requires references to non singleton instances.</span>

<span class="token keyword">type</span> UserPermissionsByID <span class="token keyword">struct</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

UserDB UserDB

PermissionsStorage PermissionStorage

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>

<span class="token keyword">func</span> <span class="token punctuation">(</span>u <span class="token operator">*</span>UserPermissionsByID<span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token function">ServeHTTP</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>w http<span class="token punctuation">.</span>ResponseWriter<span class="token punctuation">,</span> r <span class="token operator">*</span>http<span class="token punctuation">.</span>Request<span class="token punctuation">)</span> <span class="token punctuation">{</span>

id <span class="token operator">:=</span> r<span class="token punctuation">.</span>URL<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">Query</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token string">"id"</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span><span class="token punctuation">[</span><span class="token number">0</span><span class="token punctuation">]</span>

role <span class="token operator">:=</span> u<span class="token punctuation">.</span>UserDB<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">UserRoleByID</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>id<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

permissions <span class="token operator">:=</span> u<span class="token punctuation">.</span>PermissionsStorage<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">RolePermissions</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>role<span class="token punctuation">)</span>

fmt<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">Fprint</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>w<span class="token punctuation">,</span> strings<span class="token punctuation">.</span><span class="token function">Join</span><span class="token punctuation">(</span>permissions<span class="token punctuation">,</span> <span class="token string">", "</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span><span class="token punctuation">)</span>

<span class="token punctuation">}</span>That’s it! Those are the 3 levels of abstraction, the first one being the most slim, containing global state and tightly coupled logic, providing the fastest implementation and the least code to write and maintain, the second being a moderate hybrid, and the third completely decoupled and reusable but requiring the most overhead for maintenance.

Pros and Cons

Approach I: Single Package

-

Pros

- Least code, much faster to implement, less to maintain.

- No packages mean no circular dependencies to keep in mind.

- Easy for testing due to the existence of service interfaces. In order to test some piece of logic, you may set the singleton instances to any implementation you choose (concrete or mock) and then fire the test logic.

-

Cons

- Single package also means no private access, everything is accessible from everywhere, this puts more responsibility on the developer. For example, remember not to instantiate struct directly when constructor function is required in order to perform some init logic.

- Global state (the singleton instances) may create an unmet assumption, for example, uninitialized singleton instance will cause nil pointer panic at runtime.

- Tightly coupled logic means nothing can easily be extracted or reused from this project.

- Having no packages independently managing pieces of logic also means the developer must be very responsible placing every piece of code correctly, otherwise unexpected behavior may arise.

Approach II: Coupled Packages

-

Pros

- Packaging our project helps us ensure responsibility of logic per package, and can be enforced by the compiler. Additionally, we can use private access, and have control over what we choose to expose.

- The use of definition package allows for singleton instances while avoiding circular dependencies. This means we can write less code, avoid managing reference passing of instances, and not wasting any time on potential compile issues.

- This approach is also ready for testing due to the existence of service interfaces. With this approach each package may be tested internally.

-

Cons

- Organizing project in packages has some overhead, the initial implementation will probably take longer than the single package approach.

- The use of global state (singleton instances) in this approach may cause issues as well.

- The project is separated into packages, which makes it much easier to extract and reuse logic. However, the packages are not completely independent since they all interact with the definition package. In this approach extraction of code and reusability are not completely automatic.

Approach III: Independent Packages

-

Pros

- Packaging helps us ensure responsibility of logic in one package, and have access control.

- No potential circular dependencies since packages are completely independent.

- All packages are completely extractable and reusable. Whenever a package is needed in another project, it can simply be moved to a shared location and used without having to change a thing.

- No global state means no unexpected behavior.

- This approach is the best one for testing. Each package may be completely tested without depending on other packages due to the local interfaces.

-

Cons

- This approach is a bit slower to implement than the other two.

- A lot more to maintain. Reference passing means we have a lot of places we need to update when we need to write breaking changes. Also, having multiple interfaces representing the same service means we have to update all of them every time we introduce a change to that service.

Conclusions and Use Cases

Given the lack of community guidelines Go code comes in many shapes and forms, each has interesting merits. However, mixing different design patterns may cause problems. To organize this, I’ve introduced three different approaches to write and structure Go code.

So when should each approach be used? I propose the following:

Approach I: The single package approach will probably be the go-to approach when working in small, well-experienced teams on small projects wanting to achieve fast results. This approach is faster and easier to kick start, although it requires much caution and coordination when maintaining due to lack of enforcement capabilities.

Approach II: The coupled packages approach is kind of a hybrid fusion of the other two, it has the advantages of being relatively fast and easy to maintain, while having most of the enforcement capabilities. It may be used for bigger projects by bigger teams, but still lacks reusability and has some overhead maintaining.

Approach III: The independent packages approach may suit projects of a more complex nature, bigger projects, projects that are probably more long term, worked on by bigger teams, or projects that contain pieces of logic that will probably be reused later on. This approach has a longer implementation time, and takes more time to maintain.

At HUMAN, we use a combination of the latter two. We implement common libraries using the independent packages approach and write our services using the coupled packages approach. I’d like to invite you to share with us your take on Go code structuring. Do you have another approach to offer? Do you have any improvements for the approaches proposed here? Let’s hear your thoughts.