Giving Fraudsters the Cold Shoulder: Inside the Largest Connected TV Bot Attack

Read time: 11 minutesSatori Threat Intelligence and Research Team

Researchers: Dr. Mike Moran, Mikhail Venkov, Ryan Castellucci, Aaron DeVera, and Davide Mandrini

Connected TV (CTV) provides massive opportunities for streaming services and brands to engage with consumers through compelling content and advertising. Because of this opportunity, it is incredibly important for the CTV ecosystem and brands to work together through a collectively protected advertising supply chain to ensure fraud is recognized, addressed and eliminated as quickly as possible as bad actors always follow the money. Ad fraud can happen when you buy inventory through unprotected channels. Ad fraud can be eliminated quickly through protected channels where there are direct relationships, trust, and full transparency. Working together through a collectively protected supply chain will ensure the ecosystem realizes the full benefits of creating a great CTV customer experience that is ad fraud free.

A new CTV ad fraud operation—named ICEBUCKET—started in a part of programmatic advertising where the supply chain is less transparent, sellers are not reported in sellers.json files, and buyers and sellers typically don’t have a direct relationship. The bad actors behind ICEBUCKET had a good thing going until they tried to expand and scale their efforts, including the partners we protect. However, by working with our partners, we blocked the attack, protected and shared data across our partner network, and improved the efficacy of our platform to ensure we stay ahead of ad fraud and the bad actors behind it. Our success speaks to the long-term planning, processes, and practices in place between us and our partners.

The HUMAN Satori Threat Intelligence and Research team recently uncovered the largest and widest Connected TV (CTV) related fraud operation to date. At its peak, the ICEBUCKET bot operation impersonated more than 2 million people in over 30 countries. The operation counterfeited over 300 different publishers, stealing advertising spend by tricking advertisers into thinking there were real people on the other side of the screen, when in reality, these were bots pretending to be real people watching TV. The operation hid its sophisticated bots within the limited signal and transparency of server side ad insertion (SSAI) backed video ad impressions. The Human Defense Platform is able to detect this fraud scheme and protect partners from falling victim to this operation, and similar ones.

Here are the details on how the ICEBUCKET operation was detected and stopped from impacting a collectively protected supply chain. In an effort to further protect advertisers, we lay out our recommendations to the CTV ecosystem and brands to remain fraud free.

One Ice, Two Ice, 28% Ice

The ICEBUCKET operation is the largest case of SSAI spoofing that has been uncovered to date. According to our internal data, near its peak nearly 28% of the programmatic CTV traffic HUMAN has visibility into, or around 1.9 billion ad requests per day for the month of January came from this single operation.

Figure 1: percentage of programmatic CTV traffic implicated in this operation for January 2020.

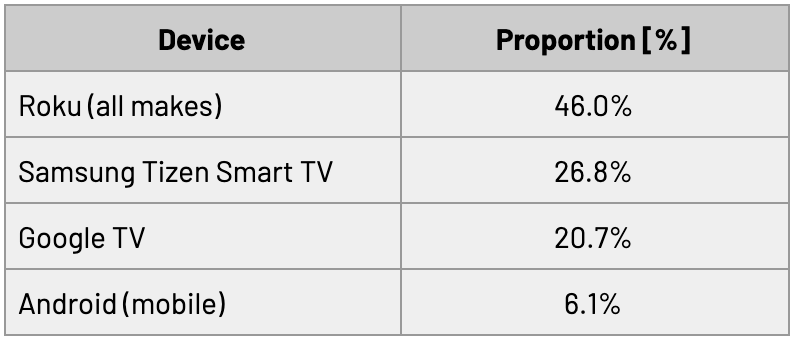

In January 2020, 66% of programmatic CTV-related SSAI traffic and 15% of programmatic mobile-related SSAI traffic that HUMAN protects was a part of this scheme. When we look at the devices the operation used, we see various CTV devices alongside the mobile traffic. The top spoofed devices in this scheme are given below. Some of the devices that the fraudsters spoofed in this operation are from discontinued product lines. HUMAN provided information into this threat to Roku, which allowed them to check the results against their internal systems. They confirmed the spoofing nature of the operation, as there was no ICEBUCKET activity on the Roku platform.

Table 1: Proportion of ICEBUCKET traffic in January 2020 for various declared devices

This operation masqueraded SSAI servers by generating traffic for fictional edge devices (specifically CTV and mobile devices) into the ad tech ecosystem. To do this, the operation used:

- More than 1,000 different user-agents, around 500 of which only appear in this operation

- More than 300 different appIDs from various publishers

- At least 2 million spoofed IP addresses from 30+ countries, where over 99% of those addresses are located in the United States

- About 1,700 SSAI server IPs located in 9 countries generating the traffic

In order to fully understand the magnitude of the ICEBUCKET operation, it’s important to have a sense of how SSAI works, the role it plays in programmatic advertising on CTV platforms, why SSAI spoofing is so difficult to detect, and what makes SSAI spoofing such an attractive target for fraudsters.

What is server-side ad insertion (SSAI)?

Server-side ad insertion, or SSAI, was developed by publishers to create a better end-user ad experience. Ads are “stitched” into the fabric of video content so that there aren’t delays or hiccups caused by launching an ad player. SSAI is commonly used for advertising on several “edge” device types, such as CTVs, smart phones, gaming consoles, and others. Delivering video ad content through SSAI offers advertisers many benefits, including user personalization and latency reduction.

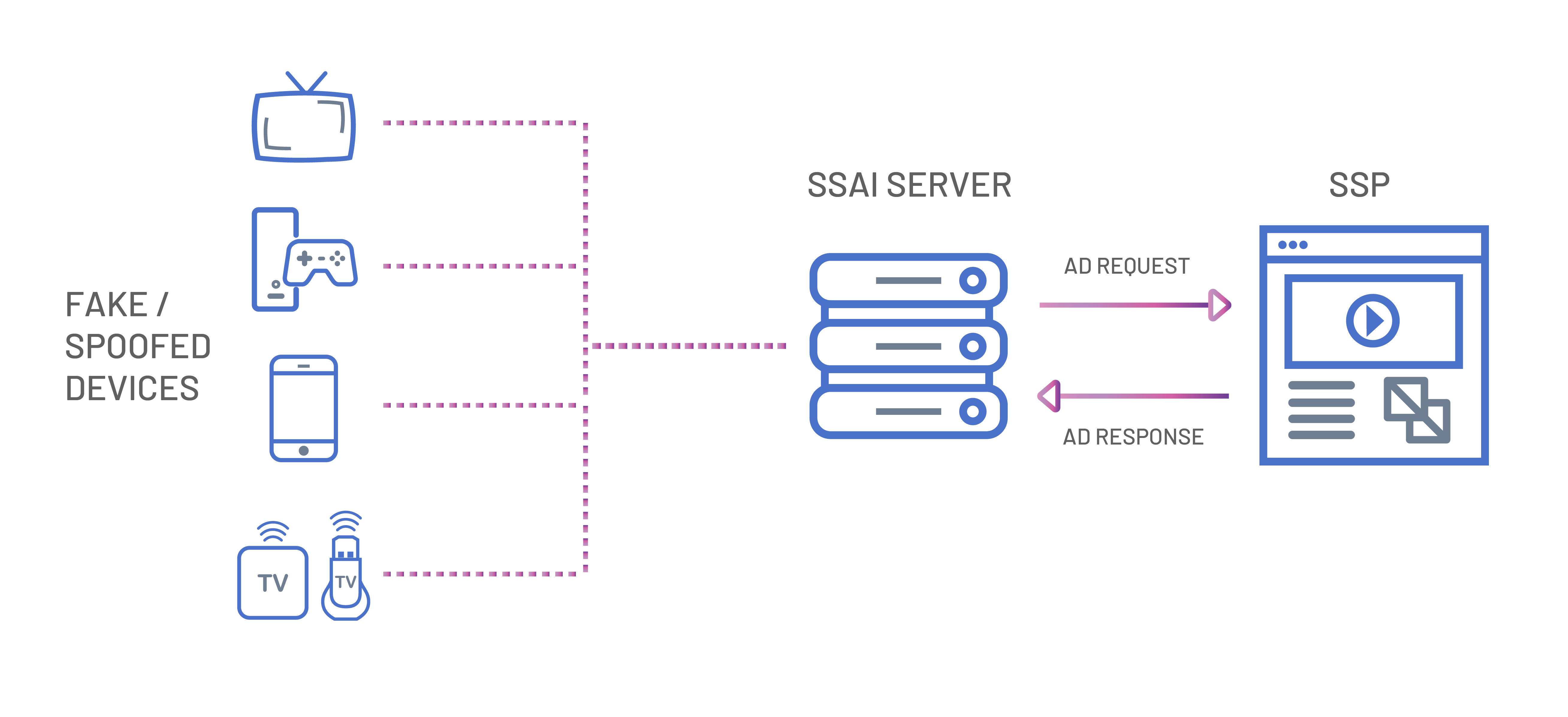

Figure 2: Schematic of how SSAI spoofing relates to the ad tech ecosystem

While SSAI is an elegant solution to ad serving, it’s still in its infancy. As with all new technologies, HUMAN can see fraudsters finding the holes in the system and wiggling their way through. Fraudsters have found a way to spoof edge devices to replicate SSAI services.

SSAI spoofing, the key fraud technique that ICEBUCKET’s operators used, occurs when fraudsters send out a bunch of ad requests from data centers for “spoofed” or faked edge devices. The data center source is expected for real SSAI providers. Rather than show the ads to humans, the fraudsters call the reporting APIs indicating the ad has been “shown”. Often, the information available to advertisers in an SSAI environment is limited to the device user-agent and IP address. This information may be sent in the “X-Device-User-Agent” and “X-Device-IP” HTTP headers, as per the IAB VAST guidelines, or through other similar headers. While falsifying this data is relatively simple, the nuance of doing so convincingly makes this a form of a sophisticated bot attack.

Advertisers pay for their ads to be viewed by a human audience that are open to their products or services. Instead, these fraudsters take the advertisers’ money and pocket it; the ads that are “served” either never see the light of day or are never viewed by a human. An audience of sophisticated bots is really just an empty audience.

The ICEBUCKET Operation

The ICEBUCKET operation presented its traffic as coming from a legitimate SSAI provider (based on the inclusion of standard HTTP headers) for a variety of devices and apps, using custom code. ICEBUCKET assembled requests for ads to be inserted into video content for viewers using CTV and mobile devices, but none of those devices or viewers actually exist. The user-agents used in the operation largely refer to obsolete device types that are no longer used in the general population, or devices that never existed in the first place. The IP addresses showed signs of being algorithmically generated to mimic desirable audiences.

These ad requests originated from a small set of Autonomous System Numbers (ASNs). Autonomous Systems make up the back-end routing infrastructure of the internet, in the same way that roads connect traffic between different cities. Each system is identified with a number, the ASN, similar in function to a postal code. While we can’t know for sure the threat actor’s motivation for using these ASNs in the operation, we can make a few comments on possible reasons. The ASNs have:

- Weak enforcement from network operators regarding malicious activity conducted from their data center

- Cheap Virtual Private Server (VPS) services available

- A large number of hosts within that IP space that are vulnerable or otherwise left open for exploitation

It is likely the actor behind ICEBUCKET operated from these ASNs due to their confidence that their behavior would not be caught. Not all traffic from these ASNs are part of the ICEBUCKET operation, as there is non-ICEBUCKET traffic from these ASNs as well.

The ICEBUCKET operation is unique in that a subset of the traffic is being generated to benefit app publishers directly through direct deals. We’ve observed cases where such publishers are mixing up organic and ICEBUCKET traffic in what seems to be early signs of traffic sourcing schemes for CTV traffic. From our observation of this “mixed up” traffic, we have two hypothesis as to why this would occur:

- Hiding the operation: By creating a subset of traffic that is not benefiting the operation directly, the fraudsters have created noise around identifying the operation. The spoofed apps are then unwitting beneficiaries to the generated traffic.

- Fraud-as-a-service: The operation is generating traffic on behalf of the app publishers. The subset of fraudulent activity becomes harder to detect, and the operation has an extra revenue source for the scheme.

At this point, we cannot make a conclusive determination between these two possibilities. There is the possibility that both of these options could be at play, depending on the particular subset of the traffic in question.

Freezing Fraudsters Out

The Human Defense Platform allows us to protect our partners by stopping sophisticated bots once we’ve accurately identified the signatures of the particular threat. By monitoring for those threat signatures in our pre-bid traffic, we can automatically block fraudulent traffic and ensure money does not go into the pockets of the fraudsters. The platform also allows us to highlight those portions of the ad-tech ecosystem where this operation is flourishing, so our partners can take actions into their own hands.

Spoofing of any kind is designed to make the spoofed entity resemble the victim (a consumer, an advertiser, an app developer – the target depends on the operation). Using several fraud markers, we can distinguish between the real, human traffic and the traffic from these spoofed devices. HUMAN is careful not to negatively impact apps that are victims in fraud schemes just because fraudsters are taking advantage of their appIDs. We work to cut the flow of money to the actual fraudsters, not the organizations they target.

.svg)

Figure 3: post-bid impressions associated with ICEBUCKET for 2020.

As noted above, ICEBUCKET is an ongoing operation. The volumes shown in Figure 3 have not gone down to zero. The fraudsters are still out there, but we are able to execute our bot mitigation and bot prevention techniques to detect them and protect against their attacks; we’re disclosing this discovery now so others can do the same. We have already rolled out defenses against similar operations, and have expanded our collective protection coverage further into the “purported SSAI” subset of our observed traffic. Our detection and bot prevention techniques are continually evolving to counter emergent threats, as well as to anticipate new ones.

Stopping the Ice Storm

Since CTV and SSAI spoofing are currently lucrative options for our adversaries due to the high CPMs on CTV consumers, we expect to see similar operations start, or that existing operations may shift from web and mobile toward CTV traffic.

There are a couple things our peers in the industry can do to try to mitigate SSAI spoofing:

- Ensure you work with a collectively protected advertising supply chain where there are direct relationships, trust, and full transparency

- Consistent appID/bundleID declarations to provide stronger links from app to publisher, such as the IAB app identification guidelines

- Consult frequently with your ad tech partners throughout the ecosystem to ensure that this new threat model is well understood by everybody in your orbit.

- Develop more standards that will increase transparency for CTV inventory such as:

- Expand the app-ads.txt standard to fully support CTV traffic

- Fully adopt sellers.json to support visibility into the entire supply chain

- Device manufacturers and SSAI providers should support the development and adoption of standards that verify the authenticity of a device (e.g. via cryptographically signing their requests). This would be a great step forward at combating device impersonation.

We’ve seen actions like this have a ripple effect. When the scheme becomes less profitable, then we have done our job: by cutting into the revenue streams of bad actors, we push them out of the ecosystem. HUMAN’s MediaGuard offering protects advertisers from falling victim to the most sophisticated bot attacks on the internet.

Education on SSAI spoofing is just the beginning – teams need to start monitoring for this behavior. The programmatic advertising ecosystem needs industry standards in order to “ice” out these fraudsters once and for all.

Appendix

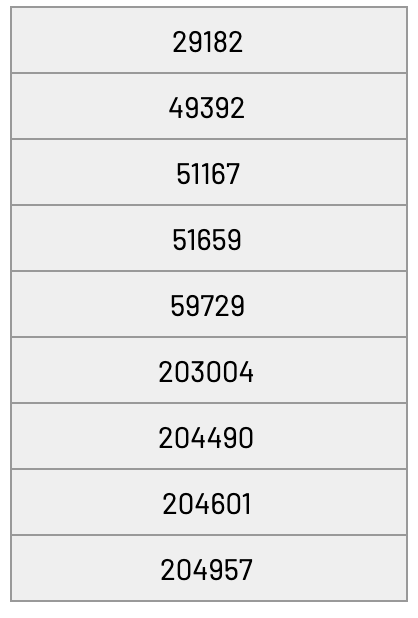

Subset of ASNs identified as the traffic sources for this operation:

Not all traffic from these ASNs are part of the ICEBUCKET operation, as there is non-ICEBUCKET traffic from these ASNs as well.

User-agents present: icebucket_uas.txt

Not all of the included user-agents are unique to the ICEBUCKET operation. Since the operation is trying to look like legitimate traffic, there are some devices represented here that will be seen outside of this operation.